Items

Tag

Interpretation

-

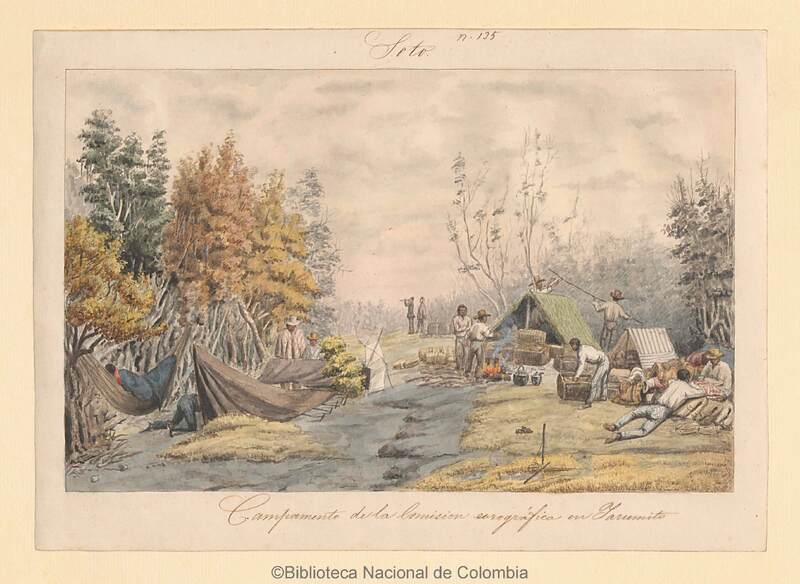

Camp of the Chorographic Commission in Yarumito, Colombia.This watercolor was created by Venezuelan Carmelo Fernández (1809–87), one of the three official draftsmen and painters of the Chorographic Commission, an ambitious Colombian enterprise to map the country, including its mineral resources, between 1850 and 1859. The Commission was led by the Italian born Agustín Codazzi (1793–1859), who involved members of his family: his wife Araceli de la Hoz served as de facto quartermaster, chief logistician, and hostess, while his daughter Constanza and her siblings assisted with reproducing maps. His sons Domingo and Lorenzo also participated in the group’s explorations. The Commission counted on interpreters, porters, muleteers, peons, baqueanos, all led by the butler José Domingo Carrasquel. The watercolor shows a character with a spyglass, presumably a naturalist, and the daily life of the camp, where it was necessary to cook, care for horses and mules, organize samples, notes and reports, as well as pitch and repair tents. Observations were not made in a vacuum, requiring numerous assistants, go-betweens, and wider support networks to make it possible to look, interpret, measure, and collect.

-

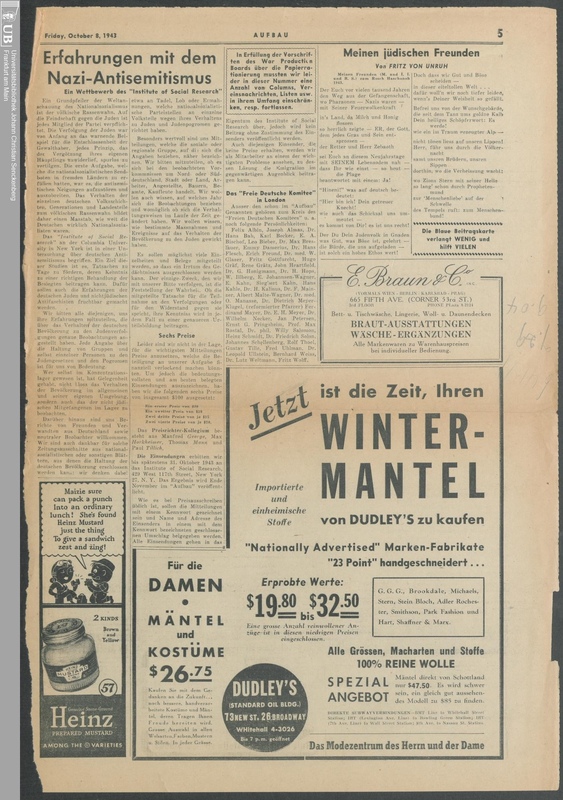

Documents of research on "Experiences about antisemitism" by the Institute of Social ResearchThe three documents displayed here – a German-language call for participation in a research contest, a circular letter to prospective contributors, and a handwritten evaluation sheet – mark the beginning of a collaborative study on antisemitism conducted in 1943 by the Frankfurt scholars of the Institute of Social Research in exile and the American Jewish Committee. Together, they record not only the launch of a research project but the material traces of how knowledge moved across languages, institutions, and political contexts during the Second World War. The magazine article solicited personal testimonies from German-speaking émigrés; the letter framed the project’s aims for contributors; and the evaluation sheet reveals how responses were assessed and categorized. Annotated and handled by multiple actors, the documents embody the layered and collective nature of social scientific production. These materials exemplify the 'circulation of knowledge' through multiple forms of translation. First, there is literal linguistic translation: German émigré scholars addressing displaced German-speaking participants while working within an American institutional framework. Second, there is methodological translation: critical-theoretical concerns about antisemitism were reformulated into empirical social research practices compatible with American scientific discourse and funding structures. Finally, there is institutional translation: a European intellectual tradition, represented by the Frankfurt School, was re-situated within American academia and the Scientific Department of the American Jewish Committee, creating a hybrid space of research shaped by exile, philanthropy, and wartime politics. The later publication of the Studies in Prejudice series (1950), including The Authoritarian Personality, would become the most visible outcome of this exchange, but these modest working documents reveal the practical, multilingual, and collaborative processes that made such intellectual transfer possible.

-

Intersex SomatotypeThis figurine was used during the Second World War to help students without clinical experience ‘recognize’, diagnose, and treat the supposedly pathological traits of intersex peoples’ bodies. As a teaching aid and visual representation, this somatotype demonstrates medical and scientific institutions’ role in solidifying oppressive biases across generations of practitioners. The project that created these somatotypes was inspired by similar models made at Johns Hopkins in the United States, showing how a transnational network of medical expertise interacted with the local practices solidifying the pathologization of intersex people among Canadians. In a 1999 interview, Marjorie Winslow (the artist) recalled that Dr. Robertson encouraged her to exaggerate the 'abnormal' qualities while sculpting the somatotypes. In this case, Winslow used actual human hair to simulate the body hair, pubic hair and moustache that physicians viewed as indicative of the supposed ‘pathology’.

-

Apkallu with eagle head from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal IIThis sculpture is of an ancient Assyrian mythological figure known as an Apkallu. Apkallu often exhibit characteristics from different groups of animals mixed together; this one has an eagle’s head and wings with the body of a human. It was extracted from the Palace of Ashurnasirpal II near Mosul and brought to Amherst College in Western Massachusetts in the mid-19th century during a period of financial, ecological, and political change. Upon its arrival at Amherst it was placed adjacent to the college’s most famous collection: the world’s first cabinet of fossil footprints. Local naturalists believed that the footprints were left by Jurassic creatures that also mixed characteristics from different living groups, combining anatomical parts from birds, lizards, frogs, and marsupials. Juxtaposing the Assyrian sculptures and the fossil footprints, later known to be made by dinosaurs, helped denizens of the area situate themselves within both human and natural history. The Apkallu was interpreted by 19th century faculty as an attempt by ancient Assyrians to symbolize the power of the Creator by combining the swiftest, strongest, and wisest animals in creation. The Jurassic footprints, meanwhile, were seen as evidence that God had created actual animals with equally fantastical adaptations. Yet, the greatest adaptations, for New Englanders, were not physical but mental, i.e. the capacity to think, act, and behave differently. By showing that they could understand a wide range of phenomena, from Assyrian myths to Jurassic creatures, they were displaying their ability to change their frame-of-mind; to show that as the world changed, they could as well. Curators, artists, and historians are now searching for ways to give these sculptures new functions and meanings. Centuries of looting and military operations have, meanwhile, destroyed many of the remaining sculptures in the original Assyrian Palaces. For the artist Michael Rakowitz, the loss of these historical objects nor their interpretation within museums can be disentangled from the loss of contemporary lives and livelihoods due to war. In response, Rakowitz has reconstructed the destroyed sculptures using intricately plastered wrappers from Middle Eastern food stuffs found in American grocery stores. By reconstructing the sculptures using mediums that families from the Middle East would have encountered when reuniting in America, these “ghosts” or “specters,” as Rakowitz calls them, remind us both of loss but also the potential for healing, restitution, and resurrection.

-

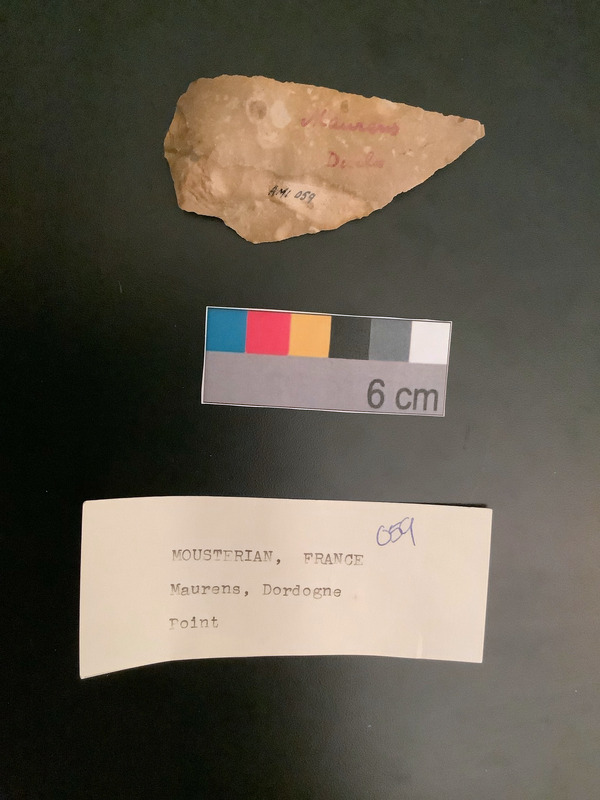

Ami Stone Tools CollectionHenri-Marc Ami made his career at the Canada geological survey, where he became convinced that all humans descended from Neanderthals. In the 1930s he created the Canadian School of Prehistoric Archeology in France and started collecting literally tons of prehistoric stone tools, notably at Combe-Capelle, at a time where no law limited the exportation of prehistoric artifacts. Ami's goal was to create collections for most Canadian university to train future archeologists. The collection speaks to the ethical issues that follow the belief in a shared human history when it comes to the collection and circulation of artifacts, notably with respect to the role it gives to Indigenous populations in human evolution and the role museums play today in the preservation of these collections that were acquired “far away from home”. Some of the tools are marked with labels indicating where they were collected. They are stored in a box along with a letter that indicates how the collection arrived at King’s College from the National Museum, after Ami's death.