Items

Tag

Geography

-

Mariner's compassThis mariners’ compass was collected by a Canadian physician working for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). Back in August 2015, I asked Dr. Simon Bryant to document his perspective of the migrant crisis unfolding on the Mediterranean. At the time, he was stationed on the 40-metre rescue vessel, MY Phoenix. This compass was found in an inflatable migrant boat after all the passengers (108) had left. Initially, I had hoped that Dr. Bryant would collect objects that spoke directly to the medical experience of migrants. He did collect various items that reflected this harrowing experience, but he did something even more important - he collected objects that related to the overall experience of the migrants. Since collecting it, the object has moved in an out of multiple contexts. Some of the objects from that initial collection have been displayed down the road at Pier 21, Canada’s Museum of Immigration. They have also been on display at Canada’s Human Rights Museum in Winnipeg. The compass eventually returned to China was part of Srajana Kaikini’s exploration of objects, relations and curatorial practice at the 2016/17 Shanghai Biennale. Back in China, the compass had returned to its context of manufacturing, as well as region of the world reputed as the inventors of the magnetic compass. When the object arrived at our museum in Ottawa, I was surprised that is was plastic. From the images I assumed that it was a brass and glass instrument found on many ships, and in many museum collections around the world. There is something telling about this plastic version of an iconic navigation instrument being used for such a desperate and dangerous voyage across the Mediterranean.

-

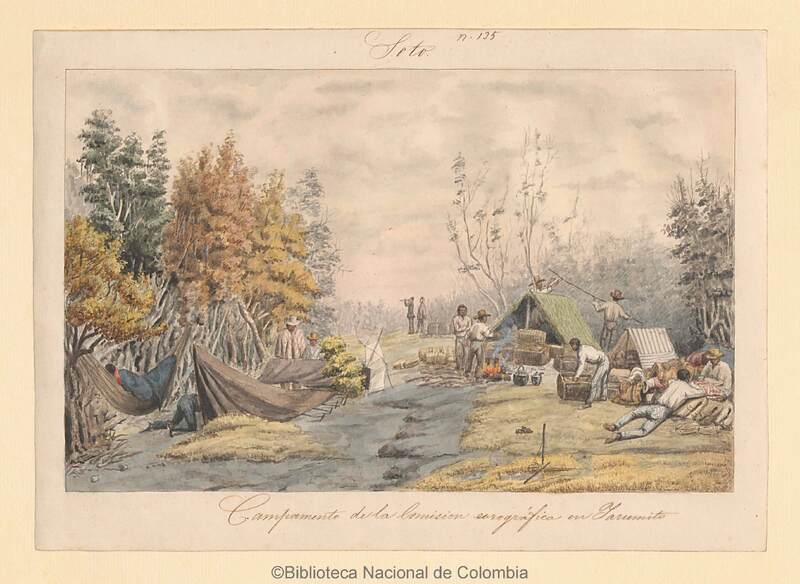

Camp of the Chorographic Commission in Yarumito, Colombia.This watercolor was created by Venezuelan Carmelo Fernández (1809–87), one of the three official draftsmen and painters of the Chorographic Commission, an ambitious Colombian enterprise to map the country, including its mineral resources, between 1850 and 1859. The Commission was led by the Italian born Agustín Codazzi (1793–1859), who involved members of his family: his wife Araceli de la Hoz served as de facto quartermaster, chief logistician, and hostess, while his daughter Constanza and her siblings assisted with reproducing maps. His sons Domingo and Lorenzo also participated in the group’s explorations. The Commission counted on interpreters, porters, muleteers, peons, baqueanos, all led by the butler José Domingo Carrasquel. The watercolor shows a character with a spyglass, presumably a naturalist, and the daily life of the camp, where it was necessary to cook, care for horses and mules, organize samples, notes and reports, as well as pitch and repair tents. Observations were not made in a vacuum, requiring numerous assistants, go-betweens, and wider support networks to make it possible to look, interpret, measure, and collect.

-

Chinese celestial globeThese globes from 1830 reflect how global exchanges produced new objects of knowledge and how the places where science happened were transformed. Qi Yanhuai, an official from Suzhou, manufactured this globe to update the imperial star catalog called the Compendium of Computational and Observational Astronomy (1723) and its Supplement (1742), the result of efforts by Jesuit and Chinese astronomers. By the 1820s the data was judged to be out of date and consequently astronomers such as Qi Yanhuai and Zhang Zuonan conducted new observations. These globes, therefore, demonstrate how Chinese users applied such translated models for their own purposes. Moreover, these globes expanded the audience for who produced astronomical knowledge. During the 18th century, exchanges occurred primarily at the Imperial court with Jesuit missionaries and other go-betweens. Yet that knowledge was limited. Only a handful of libraries had access to such printed books or manuscripts. These celestial globes aimed to distribute this knowledge more broadly through a different media and experience. They simplified computation and allowed for most educated people to participate. One remarkable feature of these globes is that they also function as clockwork devices. Created by Chinese clockmakers, these mechanisms transferred a global technology into a useful system for Chinese officials and families. The clock reported hours and time according to the traditional system of timekeeping in China, rather than simply a wall decoration. Moreover, since some globes included bells for hours of sunrise and sunset, the clocks could also be used as a practical device for bureaucratic needs to report those times to the city watch. More than just repurposing technology in a local context, Qi Yanhuai claimed that this feature was in fact what made them so useful as knowledge making devices. Although some conservatives viewed elaborate automata as wasteful and unnecessary or as appealing to base senses for popular audiences, Qi said that clockwork allowed one to check and evaluate celestial positions with just a single glance. They made calculations easier. “If your household has one, even your wife and children will be able to know the stars,” he said. Although clockwork connected this device to the world of entertainment, Qi suggested they were “Chinese instruments.”

-

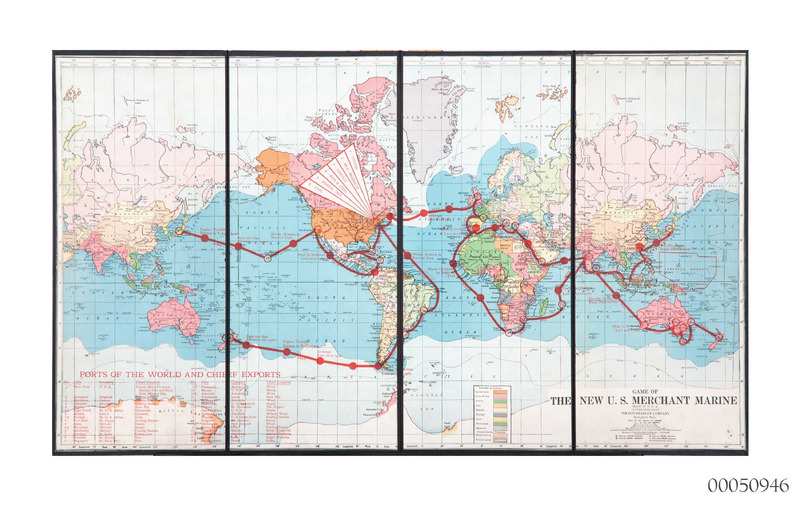

The Game of the New U.S. Merchant MarineThis game was developed as part of the publicity campaigns to build the "shipmindedness" of the modern United States under the auspices of the U.S. Shipping Board. This civilian board oversaw the massive ship building program of 1917–20 to support the entry of the U.S. into WWI; after the Armistice it promoted a maritime vision of the modern world. Geographical and economic games were an established genre in the 19th and early 20th century. This game is noteworthy for its promotion of technological change and the modern conditions of shipping—it was the opposite of nostalgic visions of geographical exploration or the dangers and adventures of a sailor's life.

-

Pocket Compass Sundial, SpanishAs with all pocket sundials, this instrument is made for travel. It carries a compass needle so that it can be aligned north-south, and its outer casing is engraved with the latitudes of many major European cities so that its shadow-casting gnomon can be adjusted as its owner moves. The predominance of Iberian cities in the latitudes list, and the presence of Antwerp as one of the four cardinal cities of Europe, suggests that it is Spanish-made and pre-dates the protestant reformation of Antwerp in the late 1560s. A second set of evidence points to the instrument’s global travels. The underside of the dial’s case has been heavily modified by a second artisan sometime after its original manufacture. A second set of city latitudes has been added, in a less assured hand. Remarkably, all of these cities are in the ‘New World’, and include both major Caribbean, Central, and South American cities (Havana; Mexico City; Lima; Quito), as well as many smaller and more obscure cities from across the north and west of the continent. Research links many of these cities to Spanish mining concerns; and so the dial appears to have been modified for use by a Spanish conquistador. Because this second latitude list cannot be matched to any known atlases or geographical texts in Spain, it is plausible that these modifications were made by an artisan working in Central or South America.

-

William Fehr CollectionThis plate, produced specifically for the Cape in Canton around the 1740s, stands out conspicuously among the William Fehr collection, inviting us to explore a largely forgotten, centuries-long connection between colonial southern Africa and the Chinese cultural world. The plate’s Cantonese painters participated in the messy transoceanic chains of production that shaped such ‘entangled objects’. They interpreted an African environment, sketched by Dutch illustrators, through the lens of Chinese expectations of elite European consumers’ tastes. The plate exemplifies Giorgio Riello’s observation that material culture can help re-articulate ‘our spatial understanding of the past in ways that are not necessarily apparent in documentary sources’. It depicts Cape Town’s iconic landscape as seen from a Table Bay littered with Dutch ships, combining several seemingly unrelated visual cultures. For example, the ‘tablecloth’ covering Table Mountain – the feature after which the Khoekhoe named the place ǁHui ǃGaeb (‘the place where the clouds meet’) – is portrayed as Chinese xiangyun (‘auspicious clouds’) over a shanshui (‘mountain and water’) scene, while the sea and sky resemble washed-out European watercolours. The scene is framed by laub-und-bandelwerk in gold and black, which was characteristic of Viennese porcelain in the 1730s, itself inspired by French Baroque aesthetics, and topped with unidentified arms.

-

Taxidermized punarés (Thricodomys aperoides)These rodents were collected in the northeast of Brazil and sent to the National Museum, in Rio de Janeiro, where they were studied alongside other animals as part of research into disease ecology. Studying rodents like the punarés was essential for understanding the endemicity of infectious diseases in Brazil and, more broadly, in South America in the 1950s. Capturing and taxidermizing these animals involved many people, spanning from hunters and peasants to doctors and naturalists, each with distinct skills and knowledge. Most of these actors were Brazilians, but South American experts from Chili and Argentina were also involved in some of these activities. As is common in the study of ecology, scholars had to rely on rural communities and their deep knowledge of local fauna.

-

"Aloes in Monkey Skin"These two items from the Kew Economic Botany Collection show the ways in which aloes were packaged for international trade. Comparing the two distinct methods used to collect, prepare, and transport these specimens demonstrates how the international drugs trade was shaped by African and Native American technologies. Medicinal “aloes” are made from the leaf gel of several different species of the plant. The drug is a black colour and looks rather like the resin of a tree. The first image (Cat. no. 36522) shows Aloe perryi from Socotra, a small island off the coast of Yemen. These aloes were considered the best for medicinal use from at least the 1st century until the 19th century. The second image (Cat. No 36520) shows aloes from the Caribbean. These aloes come from the plant now known as Aloe vera. Both these types of aloe circulated internationally, but their packaging reflects the specific technologies and environments of the places where they were produced. In Socotra, the method of making aloes involved draining the leaf sap into a monkey skin. The sap was left to harden in the sun and then packaged in the same skin for export. Although these aloes come from Socotra, they were sold to traders from western India and marketed internationally from there. This explains the reference to the “East Indies” on the label. In the Caribbean between the 17th and 19th centuries, aloes were exported in gourds, and as such were often known as “gourd aloes”. In both Africa and the Americas, the gourd is used as a container also known as a calabash. In Mexico, it was used to contain pulque, the fermented juice of the agave plant. It was the confusion between agave (also called Aloe americana) and aloe that originally gave rise to the name Aloe vera.